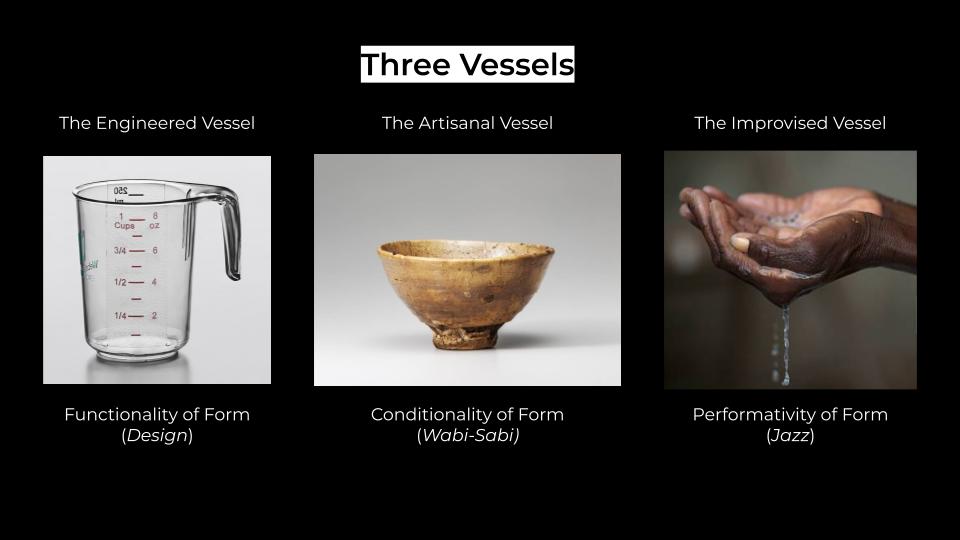

Learning to prepare dishes from my grandmother, I never referenced standard measures. My grandmother would say, “you need this much water”, and I gauged measures using my sense of hearing, sight, touch, and taste: listening for how intensely and for how long she held the faucet open to get the measure of water she needed, looking at how much water filled the pan, holding the pan while the water was added and feeling the weight of it, tasting the dish, finding it a tad too liquid, and wishing that my grandmother added bit less water than she did… But if I were to write a cookbook full of my grandmother’s recipes that people all over the planet might use, I would need to use the standard measures that many are familiar with. I would have to write, “Add 3 ½ cups of water.” Yet, even then, non-standard and anexact measures are necessary, phrases like “lower the temperature to a simmer”, “salt to taste”, “sauté till translucent”, “add the whites of three large eggs”, etc. The prevalence of standard measures, like the 8 fluid ounce cup, not only in recipe books but in all fields of human activity, is never a mere historical accident. The establishment of any and every standard measure is a remarkable social feat, involving either remarkable common efforts or remarkable impositions of systems of domination. When impositions of systems of domination are involved, the prevalence of a standard measure indexes more harm than good.